It is not the only example of a settlement according to the principle “more autonomy, but not a state”. Many statesmen and experts proposed such options as an opportunity for both sides to resolve conflict with dignity, with minimal losses both to their security and self-esteem (which is equally important). Let’s look at one more example of this kind presented by American researchers D. Laitin and R. Suny17.

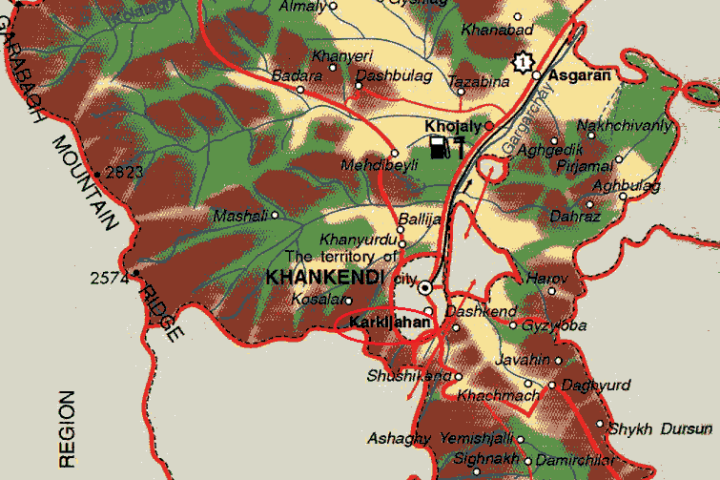

1. Karabakh de jure must remain within Azerbaijan in conformity with the principle of territorial integrity of a state and the inadmissibility of unilateral alternations of borders by force. The symbolic sovereignty of Azerbaijan over Karabakh could be represented by the Azeri flag waving over the Government House in Karabakh and by the appointment of an Azeri representative in Karabakh who will have to be approved by the Karabakh government. The formal aspect of sovereignty implies Azerbaijan’s representation of Karabakh in the UN and other international organizations.

2. The citizens of Karabakh must have proportional representation in the Parliament of the Azerbaijan Republic in Baku. The Karabakh representatives in the Parliament of the Azerbaijan Republic must have the powers to stop any proposed law that directly concerns Karabakh.

3. The establishment of full self-government of the Republic of Karabakh within the borders of the Azerbaijan Republic, presupposing the formation of their own Parliament with proportional representation of the population, the right of veto on the resolutions of Azerbaijan concerning this republic, sovereign rights of its government in issues of security, education, culture and investments in infrastructure.

4. The absence of units of armed forces and the police of the Azerbaijan Republic and the Karabakh Republic on each other’s territories without mutual consent.

5. The Armenians and Azeris living in Karabakh would have the right to dual citizenship or full citizenship in either republic with the right of permanent residence in Karabakh.

Summing up what was stated above, one can note that the variants of settlement like “more than autonomy, but not a state”, “associated state” and “common state” often have characteristics interwoven among themselves and it is difficult to draw a clear distinction among them18.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

References:

1By the way, very often, for a variety of reasons, a part of a unitary state, the population of which does not differ from the rest by nationality, often strives for self-determination (or, as it is often said, display separatism). During the last decade movements for secession with most various motivations could be observed in Italy, Indonesia, Canada, Mexico and the USA.Back to text

2What is implied is the articles by E. Kurbanov, “International Law on Self-determination and the Conflict in Nagorno Karabakh”; A. Iskandaryan, “The Genesis of Post-Communist Ethno-Political Conflicts and International Law (Trans-Caucasus as an example)”; and N. Hovhannisian, “The Nagorno Karabakh Conflict and Variants for its Solution”, presented in the book “Ethno-Political Conflicts in the Transcaucasus: Their Sources and Ways to Solve Them” (Published by Maryland University. – Baltimore, 1997).Back to text

3Halperin M., Scheffer D. Self-Determination in the New World Order. – Wash. D.C., 1996. – P. 46.Back to text

4Ibid.Back to text

5Halperin M., Scheffer D. Self-Determination in the New World Order. – Wash. D.C., 1996. – P. 46.Back to text

6Materials of the seminar “The Process of Peaceful Settlement of the Nagorno Karabakh Conflict”, Tsakhkadzor, 23-25 July, 2001.Back to text

7Luchterhandt O.Nagorno Karabakh’s Right to Independence According to International Law. – Boston, 1993.Back to text

8Luchterhandt O.Nagorno Karabakh’s Right to Independence According to International Law. – Boston, 1993.Back to text

9See Manasyan A.S.,The Karabakh Conflict: Internationally Recognized Bases of The Problem. (The Open Folder of Legal Documents). Yerevan, 2004. This author specifies that in 1918-1920 the Azerbaijan Republic not only did not have NK as its part, but had no internationally recognized borders at all – just like the other republics of the South Caucasus, it simply has not had time to get corresponding documents during its short life. Back to text

10See in this connection the statements of leading foreign specialists Khannum Kh., Eizner M., Espinel G. et al., quoted in the aforementioned article by Kurbanov E. – P. 58, 59, 60 etc.Back to text

11Sometimes the conduction of such a referendum in August 1923 in Nagorno Karabakh is even mentioned in Azeri literature. The Armenians call it into question arguing that there is no document proving the fact of the conduction of the referendum. And indeed, there is no exact data, and it is unclear how the questions were formulated and what the concrete outcomes of the referendum in figures were. (V.K.)Back to text

12A report of the Noyan Tapan News Agency, April 25, 2002.Back to text

13No matter how interesting may be the discourses of scientists and experts concerning the priority of one of the principles of international law over the others, they remain no more than discourses – they can’t be considered internationally accepted norms, the grounds for reconsidering this law, let alone its application in practice by the states. Primordially neither contraposition of these two principles to each other nor the establishment of their hierarchy is acceptable. As it was noted in the Declaration of the UN General Assembly on the Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States in accordance with the United Nations Charter adopted on October 24, 1970, “while interpreting and using the principles stated above the latter principles are interconnected and each principle must be considered in the light of the others.” The OSCE which assumed the basic role in the settlement of the Karabakh conflict displays the same approach. The Helsinki Final Act after stating 10 well-known principles especially emphasises: “All the principles stated above are of primary importance and, therefore, they will be equally and undeviatingly applied in the interpretation of each of them taking into account the others.” (V.K.) Back to text

14Unlike many mass media the authors quite correctly use this very term. In the press and in private life in connection with conflicts it is mostly spoken about refugees but terminologically it is not always correct and it is sometimes used inappropriately. In the international humanitarian law and in the legislation of many states there is a distinction betweenrefugeeson the one hand andforced migrantsordisplaced personson the other hand (the first ones moved to another state, the second and/or the third ones remain in the territory of the state where they lived). Who should help and support them substantially depends on the distinction of these categories of persons who suffered from the military conflict. It is worth specifying that the overwhelming majority of Azeri “refugees” are in fact forced migrants as they remained in the territory of their state. The real refugees are the Armenians who left Azerbaijan and the Azeris left Armenia. (V.K.) Back to text

15We express our gratitude to political analyst R. Musabekov who kindly provided us with the text of the project.Back to text

16One should not forget that the symposium in Marienhamn (Alands) was held at the time when military operations around Nagorno Karabakh were in full swing. At that period, to have big ideas about the introduction of the Alands model in Karabakh would be the acme of naivety on the part of the initiators of the symposium. To stop the war at that time, it was more important to familiarize the parties to the conflict with the possibilities of a civilized peaceful solution to the ethnic conflict similar to that earlier reached by the Finns and Swedes around the Alands. (V.K.) Back to text

17David Laitin D. and Grigor Suny R. Armenia and Azerbaijan: Thinking a Way Out of Karabakh // Middle East Policy. – Wash. – Vol. VII. – N 1. – Oct. 1999.Back to text

18At the beginning of 1996, by instructions of the new Minister of Foreign Affaires of the Russian Federation, Ye. M. Primakov, within the framework of Russia’s “shuttle diplomacy” the project of the “package” settlement of the conflict was submitted to all the three sides as the basis for negotiations. Its essence is stated in Primakov’s memoirs “Years in Big Politics” (M., 1999. – P. 408-409) the following way: The recognition by Armenia and NK of the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan was connected with the self-determination of the population of NK within the framework of Azerbaijan as a state formation with the highest degree of self-government. Practical measure from the two sides were envisaged: Baku’s consent to the liquidation of the “enclave” character of Nagorno Karabakh and the establishment of unhindered communication between Nagorno Karabakh and Armenia through the so-called Lachin corridor as well as Armenia’s consent to free railway communication between Azerbaijan and Nakhichevan. It was envisaged that Azerbaijan and Nagorno Karabakh would sign an agreement according to which Nagorno Karabakh would have its own Constitution. It mustn’t comprise clauses which contradict the basic principles fixed in the agreement between the sides (about the settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict). At the same time, the parliament of Azerbaijan must introduceappropriate changes in the Basic Law of the state. It was envisaged that the laws of Azerbaijan are valid in the territory of Nagorno Karabakh provided that they don’t contradict its Constitution and laws. Nagorno Karabakh independently forms its legislative, executive and judicial power. It will have its flag, emblem and anthem, security forces (national guards) and police. At the same time, the population of Nagorno Karabakh will elect their representatives to the parliament of Azerbaijan as well as will take part in the election of the president of the Azerbaijan Republic. The citizens of Nagorno Karabakh will have passports of Azerbaijan with special marking “Nagorno Karabakh”. Decisions of central authorities with respect to sovereign rights, security, territorial division and borders of Nagorno Karabakh will be valid only if approved by the parliament and the government of Nagorno Karabakh.

The zone of free trade with the circulation of currency of other states will be established in the territory of Nagorno Karabakh. Nagorno Karabakh will be entitled to establish direct foreign ties in the sphere of economy, culture, sport, political (except diplomatic) relations with other states and international organizations, to have its appropriate representations abroad. The return of refugees (except the zone of the Lachin corridor) and guarantees for the agreement between the Azerbaijan Republic and Nagorno Karabakh from Russia, the US and other members of the OSCE which are permanent members of the UN Security Council were envisaged.

In Yerevan this project was taken as a basis for the negotiations, but Baku and Stepanakert rejected it. (V.K.)